.

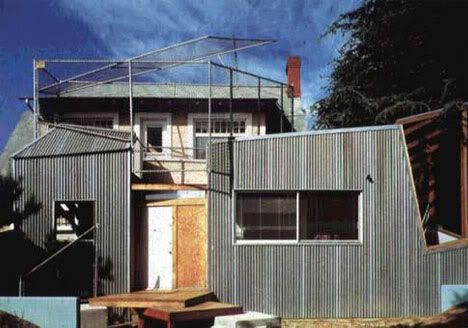

Gehry trúng giải thưởng 25-năm kiến trúc của Kiến Trúc Sư Đòan Hoa Kỳ qua căn nhà được sửa lại năm 1978 tại Santa Monica, California.

.

.

Gehry Residence | Notes of Interest

.

.

By Zach Mortice, Managing Editor, AIArchitect

.

.

.

The Gehry Residence in Santa Monica, Calif., has been selected for the 2012 AIA Twenty-five Year Award. A seemingly ad hoc collection of raw, workmanlike materials wrapped around an unassuming two-story clapboard bungalow, Frank Gehry’s, FAIA, home for his wife, Berta, and two sons found a literal, but unexpected, answer to the question of neighborhood context, and used it to forever re-shape the formal and material boundaries of architecture.

.

.

Enormously influential in both theory and practice, the home’s fundamental material modesty and formal experimentation marks a Rubicon in the history of contemporary architecture, tearing down inherited stylistic standbys to declare a new design language for the modern suburban architectural condition. Recognizing architectural design of enduring significance, the Twenty-five Year Award is conferred on a building that has stood the test of time for 25 to 35 years as an embodiment of architectural excellence. Projects must demonstrate excellence in function, in the distinguished execution of its original program, and in the creative aspects of its statement by today’s standards. The award will be presented this May at the AIA National Convention in Washington, D.C.

.

.

.

Who are we?

.

.

Quite plainly, the Gehry Residence is a suburban house totally unconcerned with traditionally pleasing aesthetics. As soon as it was completed in 1978 reactions ranged from hagiography to anathema. Over time, critical reactions mirrored the role the house would play in the larger canon of contemporary architecture. A 1979 review by New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger, Hon. AIA, recognized the house as an extremely successful provocation—if not much more. He called the Gehry Residence the most significant new house in Southern California in years, admiring its central conceptual conceit: an old house wrapped in jagged panels of corrugated metal, creating a new band of patio-like indoor/outdoor space on three sides. Windows were inflated into small skylight atriums, canted and distorted into sculptural expressions of transparent mass. A thoroughly collaged composition, plywood and (most infamously) chain-link fence punctuate the house’s rough-hewn exterior. Inside the added indoor/outdoor space, the floor was asphalt, and the now-interior wall was still the original painted (salmon-pink) siding. Throughout the interior, Goldberger appreciated the abundance of natural light and the exposed wood beams Gehry revealed after he gutted the original house, which communicate a sense of structural honesty not often associated with his work.

.

The exposed structure, chaotic fusion of disparate materials, and aggressive juxtaposition of old and new communicate a sense of real-time formal evolution and conflict, as if the building were dynamically, violently creating itself with found objects. This notion of embracing unfinished imperfection has been powerfully influential among progressive building designers, especially in Gehry’s home base of Southern California. The sculptural qualities of Gehry’s house presage the wild eruptions of form at the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and Walt Disney Concert Hall that would make him a world design icon, still recognizable under the rectilinear massing of the old bungalow and its curious new armature.

.

Goldberger was careful to note Gehry’s exacting, though superficially obscured, compositional hand. “What Mr. Gehry is saying, then, is that there can be beauty in such harsh elements when they are carefully wrought and precisely put together, that they can create a new kind of order which can yield as much physical ease and comfort as a conventional house,” he wrote.

.

By 1993, the next Times critic, Herbert Muschamp, concluded that the house was much more than a well-played provocation: It was a residence that defined modernity in built form just as Jefferson’s Monticello, Wright’s Taliesin, and Johnson’s Glass House had before it. The Gehry Residence exemplified its age because it was made of its age, cheap-looking construction, chain-link, and all. When Frank Gehry surveyed the suburban Southern California landscape where he’d built a career as a moderately successful commercial architect, he seized on the omnipresent elements that are easiest to ignore: concrete block and chain-link fence, RVs and boats on trailers hauled into driveways, and cars up on cement blocks stranded in front yards—coarse, utilitarian, and cozy, with not a brick of travertine to be seen for miles. The post-WWII exodus from central cities was carpeting Southern California in inexpensive wood-framed tract homes, their skeletons offering sweet glimpses of structural honesty and expression before being papered over in anachronistic style book patterns.

.

.

For Gehry, these were the fundamental symbols of the vast American middle class that he found himself a part of, and they had to be taken seriously and integrated honestly. Instead of the historicist styles (Tudor, Cape Cod, etc.) that still dominated suburban home building, Gehry drew from art traditions like Cubism and Pop Art, and in the process became a standard bearer for the Deconstructivist strain of architecture that gained prominence throughout the ’80s and ’90s.

.

.

But the Gehry Residence was most fundamentally derived from Frank Gehry’s own searing self-critique of who he and his economic cohort truly were—not from any external design tradition. From the house’s award submission portfolio: “I agonized about the symbols of the middle class to which I belonged, and to the particular symbols of my future neighbors. I searched for an interpretation of what I found that could suit my family, myself. I dug deep into my own history and education for cues and clues and then followed my intuitions.”

.

.

Authenticity and modernity

.

.

The Gehry Residence’s confrontational use of materials is meant as a sly comment on how homes are made and what is appropriate to make them out of. Its superficial crudeness points out the still relatively primitive way houses are built, and the upfront use of chain-link makes it harder to ignore that this ungainly material covers vast tracts of cities. The use of these types of materials has been hugely influential. The Gehry Residence has probably done as much as any other contemporary building to de-stigmatize the use of simple, raw, industrial materials for the bourgeois urban class.

.

.

As a commercial architect, Gehry had only started using such inexpensive materials to please clients on tight budgets, and it’s a supreme irony of his career that once he took this approach to it apotheosis in his own home, he soon found some of the world’s largest, most lavish commissions headed his way. Gehry responded in kind by building in titanium.

.

.

And from the glitz and shimmer of his Guggenheim at Bilbao, it’s easy to forget the fundamental humility of the Gehry Residence. Whether you question its formal resolution or not, it’s an authentic attempt to define the contemporary American suburban architectural condition—a building context many architects don’t touch. It uses modest, inexpensive materials to renovate an existing home on a typical suburban block. Architects stifled by the recession might be comforted to know that for her book Conversations with Frank Gehry, the architect told Barbara Isenberg that purchasing the house and renovating it cost only $260,000.

.

.

Despite its brazen forms and material selections, Gehry has denied designing his house as any kind of built manifesto. It’s class conscious, but only in the sense of attempting to define the position of the largest, most “ordinary” species of American. Over the years, Gehry has added another bedroom and turned the garage into flexible living space for his children, now grown. His aspirations for the house are as uncomplicated as those of his neighbors. “All in all,” he wrote in the house’s submission portfolio, “the house has graciously adapted to our changing family.” With his home, Frank Gehry may have defined a new modernity in architecture, but he’s kept the brick fireplace all along.

.

Photo Credit

.

© Gehry Partners LLP

.

.

.

.

2012 Institute Honor Awards for Architecture Jury

Rod Kruse, FAIA, Chair

BNIM Architects

Des Moines

.

Barbara White Bryson, FAIA

Rice University

Houston

.

Annie Chu, AIA

Chu & Gooding Architects

Los Angeles

.

Dima Daimi, Assoc. AIA

Rossetti

Farmington Hills, Michigan

.

Harry J. Hunderman, FAIA

Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc.

Northbrook, Illinois

.

Scott Lindenau, FAIA

Studio B Architects

Aspen, Colorado

.

Kirsten R. Murray, AIA

Olson Kundig Architects

Seattle

.

Thomas M. Phifer, FAIA

Thomas Phifer & Partners

New York City

Seth H. Wentz, AIA

LSC Design, Inc.

York, Pennsylvania

.

.

.

Khi căn nhà này được sửa xong, có nhiều hàng xóm ghét tới độ lái xe đi ngang qua, bắn súng vào nhà... !!! vì nó qúa xấu và làm giảm giá trị của nhà hàng xóm !!! Gehry rất có tài chọc tức thiên hạ.

.

.

.

.

.

mấy tấm hình trên, chưa cho thấy sự "kỳ cục" của căn nhà sau khi được sửa và xây thêm, phía góc cạnh khá xấu không có hình cho thấy. Frank Gehry sau này có những sáng tạo kiến trúc, theo nhiều người nói: cứ lấy tay bóp vò tờ giấy cứng, rồi buông ra, nó ra hình thù gì, thì đó là sáng tạo của Gehry.

..

.

.

.

Disney concert hall của Gehry tại trung tâm thành phố Los Angeles.

.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment